The “Power Alley,” a.k.a., Troubling Interactions Of Subwoofers

Opposing subs can create regions where LF energy is too hot.Here’s the explanation and some solutions. By Joe Brusi

Subwoofer cancellation is not an unusual occurrence, particularly for open air applications. Performance is not good in some audience areas. Sometimes a specific model of sub gets the blame. The underlying problem is that of the interaction between subwoofer stacks located on each side of the stage.

So let’s shed some light on this problem and remove part of that “veil of mystery” that surrounds it, due mostly to the lack of published material.

What’s Going On?

Whenever we have loudspeakers located on both sides of a stage, there’s always interference between them, assuming, that is, that they carry the same signal.

As seen in Figure 1, when the distance to both sides is the same, sound from both sides arrives at the same time. As we are closer to one side and farther from the other, sound from one of the sides arrives before theother. This time arrival difference produces comb filtering effects.

When two signals, one of which is delayed in time with respect to the other, are added, we get the well-known comb filter effect. Thisis due to destructive interference. Figure 2 shows the resulting frequency response of summing two signals with a time difference of 7milliseconds, which is equivalent to 2.5 meters (8 feet). The spacing between the troughs (“combs”) increases as frequency goes down.

Absolute cancellation occurs at frequencies where the time arrival difference results in 180 degrees of phase difference between the twosignals, so these frequencies get wiped out. As any frequency responseanomaly, the audibility of comb filtering is a function of the width ofthe troughs. These are wider for the lowest frequencies, which makes comb filtering more audible for those frequencies.

Comb filtering cannot be corrected by using equalization, since there is absolute cancellation at the bottom of the troughs. Only if one ofthe two signals is greater in level than the other will the effect bediminished and the combs reduced in depth.

The Problem

If the time arrival difference were constant, we would simply compensate by delaying one side and go home happy. However, each listening position(except the center line) gets sound arriving from each side with a different delay between them, which means that delaying one subwoofer stack wouldjust shift the sweet spot elsewhere.

Also, the combs are in different frequencies at different positions, which means that the frequency response is widely different through out the audience area. The problem is not as bad with mid and high frequencies. First, because the troughs are narrower, and hence less audible,and second, because the zones created are smaller. Withbass frequencies, one can literally walk the different cancellation areas, whereas the high frequency zones may be sosmall that the left and right ears do not share zones, so thatthe effects of cancellation are not as destructive.

Also, sources are more directive as frequency goes up. This means that when the audience is closer to one of the sides,they tend to be to some extent inside the main coveragebeam of one side of the system and outside of the other, socomb filtering effects are reduced.

But with subwoofers, the situation is a nightmare. Combsare wide and very audible. Kick drum just seems to disappear in some places. And, since the wavelengths involved are solarge (e.g., ~5 meters or 16 feet at 70 Hz), zones are enormous.

Because subwoofers are omnidirectional below, say, 150Hz, the whole audience area is within coverage of both sides of subwoofers. All types of subwoofers suffer from interference effects nomatter what the type (direct radiating, folded horn, etc.) or brand.

The result is the “power alley,” which describes the fact that only a narrow center line of a left and right subwoofer configuration gets interference-free bass.

Modeling (Getting The Finger...)

Let’s use electro-acoustic modeling to reveal the phenomenon.

The following predicted coverage maps are very closeto what happens in real life in open-air applications. Closed spaces add a reverberant field that tends to smooth out coverage out, along with room modes, which create additionalzones of their own.

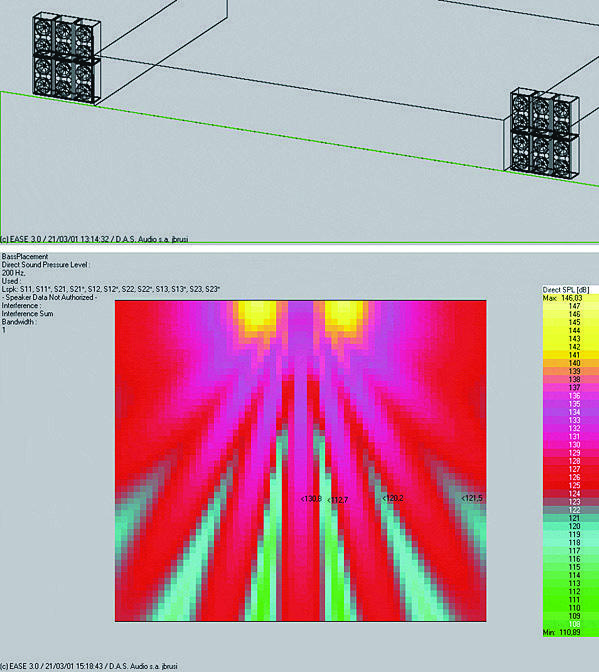

We’ve placed 3-high x 2-wide stacks of double 18-inch subs on both sides of an 8-meter (27 feet) wide stage. An audience area of60 meters (200 feet) wide and 52 meters (175 feet) long is used.

The first coverage map (Figure 3) corresponds to 100 Hz.We have switched on just one side of subwoofers just to see what happen when all our bass emanates from a singlestack. Sound pressure level expands smoothly in a way thatis close to the distance-squared law. So far so good.

But problems knock on our door when both sides are on (Figure 4). Also at 100 Hz, we can now see some kind of alien hand with five fingers. These are maximum pressure lobes, where the phase difference between the left and the right sides issmall. The areas between the lobes represent cancellation. Level readings show levels down 20 dB from the lobes. That means 100 Hz pretty much walks out on us.

O.K., so at least some folks are enjoying good bass, right? Wrong. Areas where the 100 Hz are in phase will have other frequencies out of phase, so there aren’t any“good” areas (except for the center line). Naturally, somefrequencies are more important than others when dealing with bass guitar or bass drum, so our problems will be more evident in some areas thanothers.

Figure 5 shows what is taking place in the location seen on Figure 4, whichis 4 meters (13 feet) off to the side. On the top part we see that the closestgroup of subwoofers arrives about 2.5 milliseconds (ms) before the other. On the bottom part, we see the resulting frequency response, where the first trough occurs at about 100 Hz.

The following illustrations (Figures 6-8) show modeling for 80, 63 and 50 Hz, respectively. Note how the number and location of the lobes varies with frequency.

So, Where Is That Alley?

For each frequency, we have a map with fingers. If we sum several frequencies and plot them on a single map, the alley emerges, since it represents the only locations where bass sums coherently at all frequencies.The width of the alley depends on the spacing of the subwoofers – as the two sides of subwoofers increase in spacing between each other, the alleywill narrow.

Figure 9 shows the alley for two single subwoofer boxesspaced 14 meters (47 feet). It’s not as obvious graphically as it is audibly, but it can still be distinguished as an approximately 4 meter (13 feet) band with more intense color.

Conclusion

The only real way to avoid the power alley is to place all subwoofers in a single location. With smaller scale applications, placing all the subwoofers in the center is normallynot a possibility, but larger shows may benefit from flyingsubwoofers in the center.

It’s important, however, to understand what is happening, so as not to blame the loudspeakers. And being aware of the zones that get created before making mixing decisions.

For instance, if the front of house console is located in the center, we couldchose a mix that’s somewhat bass-heavy when listened to along the center line. Meanwhile, off to the sides, destructive interference will kick in andestablish some frequency balance between the low frequencies and the rest of the system.

JOSÉ (JOE) BRUSI is an independent electroacoustical consultant(www.brusi.com). And thanks to Joan La Roda for the field phase measurements of the alternate face-to-face subwoofer configuration.